Carolyn Elkins now assistant professor at Harvard University, spent ten years researching the real history of the Mau Mau insurgency in Kenya and the systemic brutality that British colonial bureaucracy put it down. Elkins says: When I presented my dissertation proposal to my department in the winter of 1997, I was intending to write a history of the success of Britian’s civilizing mission in the detention camps of Kenya” What drew her into the lower depths of the true history of the Mau Mau rebellion was the absence of records about it. The author found obvious gaps in the usually meticulous records, some missing and others “still classified as confidential some fifty years after the Mau Mau war.”

The Kikuyu people in Kenya found their land being confiscated and their labor coerced by British “development” projects such as the building a railroad, the growing of cash crops to repay British taxpayers for this expensive scheme, and ultimately the influx of British settlers to exploit land use and native labor. Some thirty thousand “coolies” from India were imported to build the railroad, many of whom were killed or maimed in the back-breaking work. Completed in 1901, the Uganda Railway consisted of hundreds of miles of track stretching from Mombasa to Lake Victoria and beyond. For 40 years the successive governments turned their backs on the Mau Mau, as the movement remains banned by Kenyatta government and Moi government. The armed movement emerged in 1950s in obvious protest, colonial land alienation, economic inequalities and political oppression under British rule. As of 2021 non of the movement’s grievances were solved adequately as the first Kenya’s president entered into a secret agreements before independence to protect British’s interests on land after he became president. According to some critics, president Kenyatta was being prepared by British to become first president of independent Kenya. Jomo Kenyatta, even though knew nothing about Mau Mau rebellion, the British used him to trick out Mau Mau leaders to their deaths.

Outlawed in 1952, mau mau was crushed in a brutal way campaign in which by the end of an emergency some 300,000 Kikuyus were unaccounted for. It’s leader Dedan Kimathi was killed in 1957. In many occasions Kenyatta vehemently disowned Mau Mau activities.

In 1963, Kenya became independent with Jomo Kenyatta as founding leader. The new government was made up by so called “moderates”, rather than the “radicals” as Mau Mau leaders advocated.

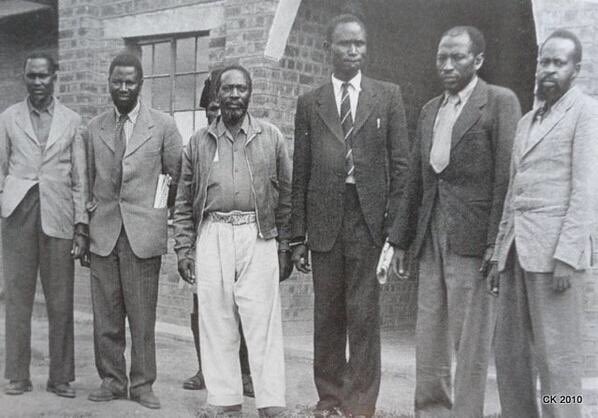

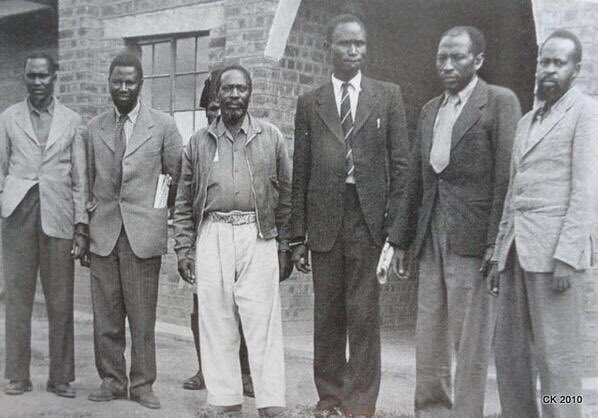

Decades later, in 1988, Itote, 66, underwent a surgical procedure to retrieve from his neck a bullet, which was donated to the National Museums of Kenya|photo|Kenyan history archives.

Kenyatta’s relationship with the movement was ambiguous. In 1952 he was arrested on suspicion of being one of its leaders. However, after the independence he was continuously pleading to “forgive and forget the past .” He continued to describe them as a “disease” and they remained banned under Kenyatta and his successor Daniel arap Moi.

In 2003 Kenya’s third president, Mwai Kibaki, lifted the ban on the movement. For many, the 40-year clampdown meant its contribution to Kenyan independence had been actively erased from national memory since independence.

The reasons why Kenyatta and Moi’s governments did not want to talk about mau mau is not a mystery, why did Mau Mau freedom fighters failed to pursue their original revolutionary goal after the independence as they saw Kenyatta inherited and opted to conserve the colonial government legacy? From the book Power and Presidency in Kenya: the Jomo Kenyatta Years, 1958-1978, suggests some of the reasons.

Meru district stood out as a sensitive area during early years of Kenyatta presidency. In Meru, Mau Mau fighters refused to surrender. Whereas Mau Mau leaders in Central Province had either been killed or tricked to surrender. Field Marshal Mwariama, Field Marshal Baimungi Marete and General Chui (originally from Central Province) were among them.

Mau Mau was a threat to a new regime and so the movement remained closely monitored by the government. In a bid to neutralise the movement, ministers and government officials repeatedly visited Meru district offering amnesty for those who would surrender. Police action to clear the forest to find the fighters deemed ineffective.

At the end the government choose to lure out the remaining leaders, or target and kill them.

Mwariama finally surrendered early in 1964. The government decided to use him as intermediary to negotiate with Baimungi and Chui in vain.

The original demands of remaining Mau Mau remained intact, land. They demanded the land should be redistributed for free. But the Kenyatta was driving the policy he agreed with British before independence , “willing buyer, willing seller. ”

On 26 January 1965 Baimungi and Chui were both killed by police.

The Ameru people were settled down by Kenyatta as he appointed Jackson Angaine as powerful land cabinet minister. Angaine was in close contact with Kenyatta about the situation in Meru. Angaine had no relationship with Mau Mau and Kenyatta knew exactly that and his appointment send positive message to Ameru people They would believe that the minister in charge of land redistribution was a local follower of the movement.

And so the “willing buyer, willing seller” land policy could quietly go on. The British government was relieved that there would be no radical land redistribution that could undermine its interests in Kenya. The new Kenyan government officials could get British loans to buy colonial land and strengthen their control over the country’s main economic resource, as Kenyatta and his close associates bought the land and subdivided them among themselves and financially stable Kenyans and firms bought the rest. Left out of the equation were the landless poor people who would have to wait longer for the promise of land to be fulfilled.